Professor Karen Nelson-Field

Source: WARC Exclusive, June 2020

At the moment, media is sold on opportunity or potential to view rather than whether someone has actually seen the ad or not – as it turns out, many don’t see it, yet advertisers still pay.

- Consumer behaviour is part science, part unexplainable – the science part is this: when no attention is paid, ads have no impact.

- Impression reform is needed to move a measured impression from an ‘Opportunity to See’ to a ‘Verified Human View’ – this is a big step up from what we have now.

Planning for Attention

This article is part of a series of articles from the WARC Guide to Planning for Attention.

Why it matters

If we can’t show a link to incremental value, what does attention measurement offer that is different? If we are asking advertisers to move towards an attention economy and away from traditional buying measures, we owe it to them to define its value.

Takeaways

- Having simple data, independent of the platform owners, that tracks human viewing and can call out platform (and creative) deficiencies, is both valuable and incremental to current measurement.

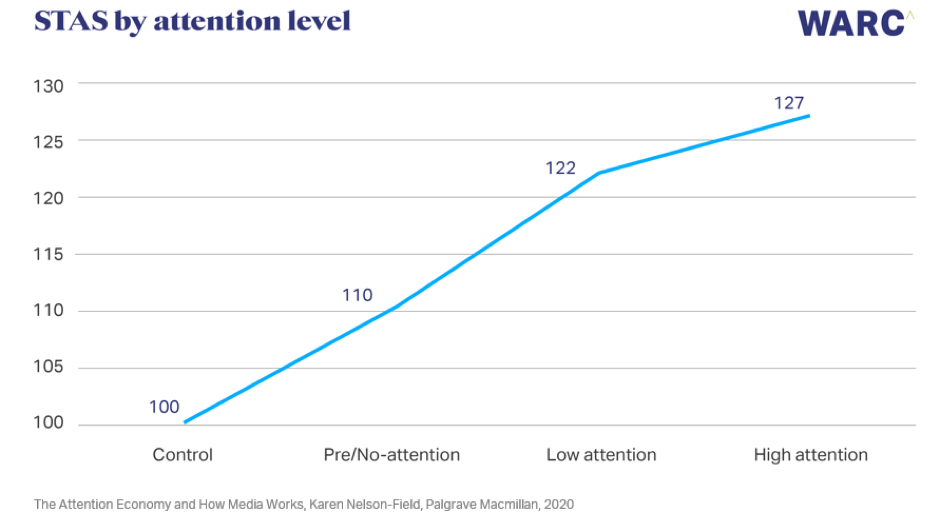

- In our data we find a relationship between visual attention and incremental brand choice – Short Term Advertising Strength (STAS). This is an extraordinarily important point given advertising is not persuasive and advertising effects are generally small.

- Attention data can be fused with other data for deeper analysis or it can be used to weight outputs in buying systems and add fairness to the game.

Advertisers look around you; it would seem that attention, as a measure of ad impact and ad delivery, has reached ‘new-black’ status. What I love about new-black in this context, is that actual human viewing behaviour is getting the focus it deserves. What I hate is that as attention measurement moves towards mass-market acceptance, and advertiser money begins to flow, opportunistic purveyors surface and the ‘what attention is and what it is not’, the ‘how it should be measured and how it should not’, becomes a bit grey.

Media trading should be fair an accountable. We know from our research, and others, that human attention is highly valuable and will aid in driving fairness and accountability. But grey is just a watered-down version of black. So, if we are asking advertisers to move toward an attention economy and away from traditional buying measures, we owe it to them to define its incremental value.

Attention and impression reform

Let’s begin by drawing a line in the sand on what it means to use attention as a supplementary layer for business intelligence and/or buying systems. With metrics it’s easy to confuse what we ‘want’ with ‘reality’. We ‘want’ attention to be a complete picture of the consumer brain and we ‘want’ attention to show a true causal link to sales. But the reality is attention measurement at scale doesn’t do either of these things; it measures other things of value.

On understanding a consumer’s brain, biometric technologies (e.g. fMRI) have delivered case evidence into the processing of advertising (http://web-docs.stern.nyu.edu/marketing/RWinerPaper2015.pdf) But for attention to become ‘tradeable’, we need a broad-reaching, always-on, scalable collection. The best technical advances to achieve these things include, facial detection (is a face present), facial recognition (is this face different to the last one), and facial coding (emotion AI) delivered via an untethered interface. Some would argue that facial coding gives rise to the ability to understand brain activity, but I suggest we are a long way from that. These technologies can measure whether someone is present, looking (or not) at advertising and have a smile on their face. Visual attention technologies currently do not tell us whether the Hippocampus lights up while watching TV.

Simply knowing if someone is present and whether they are looking (or not) at advertising is light years ahead of the current impression system. At the moment, media is sold on opportunity or potential to view rather than whether someone has actually seen the ad or not. As it turns out, many don’t see it, yet advertisers still pay. Research from those of us who collect visual attention shows that both the TV ratings systems and digital impressions tell us nothing of the reality of a view, nor do they show how fleeting and un-sustained attention really is. Having simple data, independent of the platform owners, that tracks human viewing and can call out platform (and creative) deficiencies, is both valuable and incremental to current measurement.

Beware the attention proxies

Buyer beware! In the trade-off between the wants and technological limitations, attention proxies have surfaced. When something is hard to measure we reach for the easy, and typically, substandard proxy. Some of these proxies include device data such as ad duration, ad pixels on screen, hover rates etc. While we know some of these things mediate attention (we collect them too), they can also measure distraction away from the screen—the antithesis of attention. The result is more technical data around the opportunity to see, and the attention they offer is assumptive. But, when these data are supplemented with facial data, the depth of inquiry can be vast.

Self-reported ad engagement, in particular recall, is a common and easy-to-collect proxy. Proponents tout that recall represents explicit memory and resulting incremental sales impact. In reality it does the former but not the latter. In terms of sales uplift, what recall does reflect is previous brand usage and brand size. In two recent large-scale collections of our own we added recall survey measures to the back end of our typical attention collection (we always collect brand usage as a sample validation) to cross check the relationship between recall and choice (24,000 ad views, 2 countries, 4 platforms). In our studies, respondents are exposed to a number of ads in real-time while facial footage is collected via the device camera for our attention models; after the viewing session we collect brand choice from a virtual store. In line with literature, our data show that brand choice and previous brand usage are related, we find that heavy buyers are 9x, and medium buyers 3x, more likely to choose the brand compared to light buyers. And it shows that recall is related to brand choice, accounting for about 35% of the variation in choice. But, also as expected, we can see that big brands (as defined by a market share baseline, not our own interpretation) account for around 95% of this variation.

What recall actually tells you is what you should already know from reading anything Andrew Ehrenberg wrote— big brands have more buyers who buy you more often and notice you more. You could predict recall from your penetration and loyalty data. So, using recall as a proxy for attention to understand platform effectiveness is flawed when multiple brands are exposed in one viewing session or across platforms. This is what happens when market-share baselines are not applied to analysis (and this is why this data could never be applied to business intelligence and/or buying systems). Regardless, it’s a common belief that recall is a necessary condition for a change in behaviour or attitude, suggesting that the purpose of an ad is to persuade someone to buy and that high levels of recall means additional sales will surely follow. There is little to no evidence that an incremental sale will follow, and given advertising is not persuasive, there is actually more evidence that it won’t.

Attention and incremental sales

Our data show no evidence that higher recall leads to incremental sales. When a market-share baseline is applied we find no relationship at all between recall and brand choice (called STAS once a baseline is applied). This is important. Recall tells you exactly the level of attention and brand choice expected given your market penetration, it rarely tells you whether your ad will be successful in driving sales uplift over what is expected.

Short Term Advertising Strength (STAS) is calculated by determining the proportion of category buyers who chose a specific brand having NOT been exposed to brand advertising, and comparing it to the proportion of category buyers who chose and WERE exposed to the same brand advertising (test group). A score of 100 indicates no advertising impact in that those who were exposed to the advertising were just as likely to purchase as those who were not.

To reiterate, in our data we find no relationship between recall and STAS, but we do see a relationship between visual attention and STAS. This is extraordinarily important. Given advertising is not persuasive and advertising effects are generally small, we really can’t expect more. Is the relationship perfectly linear? No. Is it causal? No. But beware of researchers (in wolves clothing) who claim they can fully explain why a human buys a product. Consumer behaviour is part science, part unexplainable. The science part is this: when no attention is paid, ads have no impact.

As part of the Dentsu Attention Economy Phase 1 collection in 2019 (3 countries, 3 platforms, 17,000 video ads), we found that low-attention processing delivers more value than most people give it credit. That the greatest uplift in sales impact occurs when a viewer moves from a pre-attentive state (non-attention) to low attention. Let’s be clear here, high attention still drives the greatest impact in absolute terms, but we see that the biggest jump in STAS happens between no attention and low attention. This is why attention is related to STAS and recall isn’t. Recall is a measure of explicit memory, whereas visual attention can measure both—implicit and explicit memory (technology dependent).

If the biggest impact of STAS uplift comes from low-attention processing, something recall doesn’t measure, the inadequacies of recall become apparent. Recall is not suitable for measuring implicit memory where viewer attention is less concentrated and under the threshold of full consciousness.

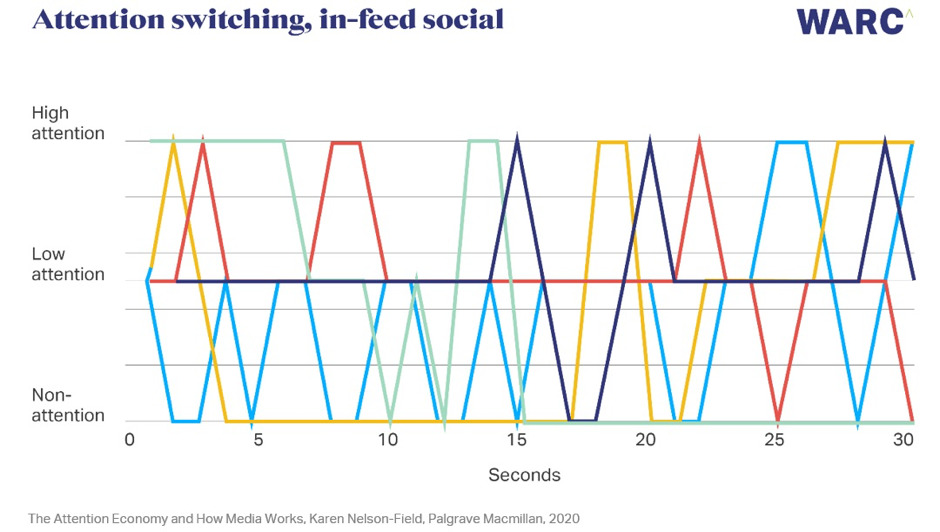

We can also see that viewers switch, frequently and abruptly, in and out of focus. So it’s just as well low attention offers value to incremental sales given more of our viewing seconds occur in this ‘zombie’ low attention state compared to highly sustained eyes-glued state. Levels of attention to advertising are a far cry from the romantic notion held by decades of advertisers. Fortunately, simply noticing can nudge a sale.

Moving forward without grey

This paper was inspired by a recent discussion about the future application of attention measurement with members of The Attention Council. It made me think about how to articulate the incremental value of (appropriately collected) visual attention and what it offers advertisers above other measures. Given the back- end of the technology and the long road of measurement evolution to date, the answer is both simple and extremely complicated.

If we want to move forward with impression reform, without grey, the industry needs a simple and transparent way to both understand and transact with this type of data. So, what incremental value does it offer advertisers?

My personal top three:

- Impression Reform—Moving a measured impression from an ‘Opportunity to See’ to a ‘Verified Human View’. This is a big step up from what we have now.

- Incremental Sales—Visual attention measures implicit (and explicit) processing and is linked to incremental sales.

- Supplementary Data—Attention data can be fused with other data for deeper analysis or it can be used to weight outputs in buying systems and add fairness to the game.

These three things alone make an economy where media impressions are based on attention, a sensible one.