First Published by WARC Exclusive, December 2020

Author: Professor Karen Nelson-Field

CEO and Founder, Amplified Intelligence

Advice on how advertisers can practically apply consumer attention data to improve marketing effectiveness.

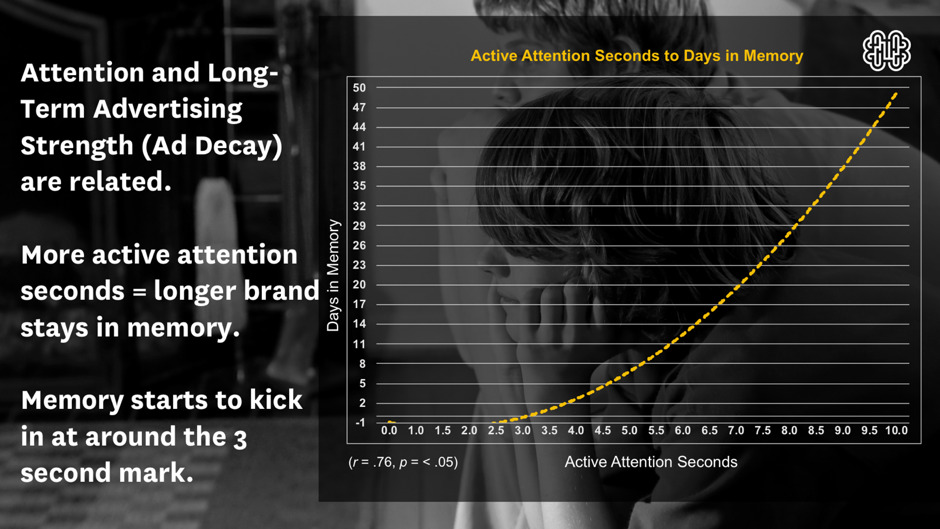

- Attention and ad decay are related: the more Active Attention Seconds paid to an ad, the longer the brand stays in memory.

- Two seconds of attention is not enough. You have to look at something to process it, but processing what you are looking at takes time.

- View duration is a poor proxy for attention and can as easily capture consumer distraction as it can capture attention.

Why it matters

If applied properly, attention can act like grocery unit pricing and provide a missing ‘relative quality’ layer in media planning, helping advertisers to understand performance of different platforms using a common metric of value.

Takeaways

- Current net reach includes non-attention and passive attention, even if the impression is viewable by MRC standards. By using Active Attention Seconds as a metric, brands can gain a more accurate picture of campaign reach.

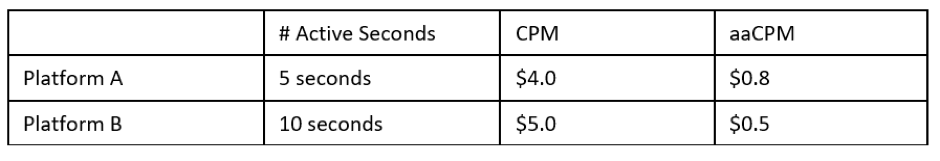

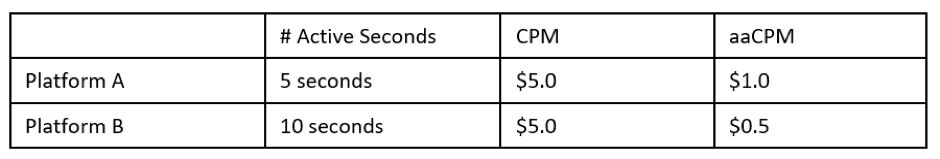

- The implementation of a common currency like aaCPM (Active Attention Seconds CPM) can help to identify whether performance differences between platforms are accounted for by cost.

- Attention data can feed an understanding of different attention environments in the creative planning process, including brand distinctiveness and whether the campaign needs to communicate new information.

An industry comes together on the future of measurement

The WARC Guide to Planning for Attention (June 2020) was an important edition for our industry and I genuinely loved being a guest editor. I wanted the Guide to act as a seminal piece for our industry, so I invited industry experts to discuss key structural factors affecting an industry on the precipice of change.

What was most evident is that there is a collective passion from industry leaders to bring balance, fairness and transparency to media trading. Equally evident was the resounding belief that independently and ethically collected attention metrics can measure quality and can help to regulate our broken advertising ecosystem by calling out differences in platform value that can affect trading.

New attention findings to support the application of attention metrics in 2021

The Guide to Planning for Attention threw real light on an industry that was ready to acknowledge that attention matters to ad effectiveness (as measured by many behavioural outcomes) and that no attention means no advertising effectiveness is possible. It might be stating the bleeding obvious, but sometimes that is what is needed.

Adding to those industry findings, here is a summary of some of our most recent work.

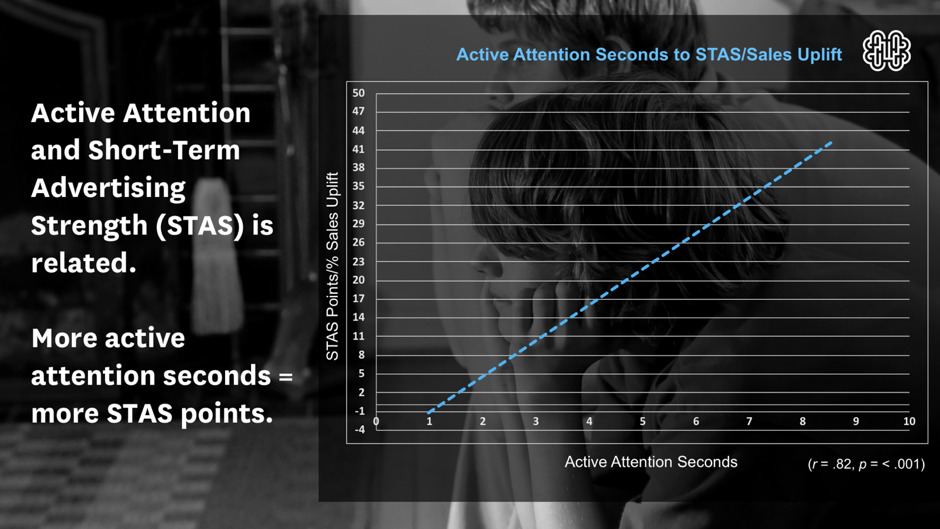

- Human attention is a pre-curser to ad impact (short-term ad impact).

While this is not technically new to us, we have refreshed the data with three additional countries because generalisation is the key to meaningful results. Our regression shows there is a strong and significant relationship between Active (eyes-on-ad) Attention Seconds and Short-Term Advertising Strength (STAS). (STAS is an index between those who were exposed and bought and those who were not exposed and bought.) This means when active attention seconds goes up, so do STAS points (r = .82, p = < .001). Not surprisingly, the analysis shows the inverse is true, that if no active attention is gained, we can expect zero uplift (see Fig 1). It’s hard to believe that people find this hard to believe, and it is probably time to accept that human attention is a pre-curser to ad impact.

- Human attention is also a pre-curser to memory retention (long-term ad impact).

The number of Active Attention Seconds matters. We see that the more Active Attention Seconds paid, the longer the brand stays in memory, i.e. attention and ad decay are related. We can also see that memory retention doesn’t kick in until an ad is seen for about three seconds, after which on average every active attention second leads to an average three days in memory.

- Two seconds is not enough.

This finding follows directly from the last, the number of Active Attention Seconds matters. A blunt reminder that two seconds of attention is not enough (see Fig 2). You have to look at something to process it, but processing what you are looking at takes time. We see that two Active Attention Seconds can generate some STAS points (on some platforms), but sales uplift grows as time passes. The difference between brand choice impact above and below two seconds is sizable.

This should not be overly surprising, there are many studies other than ours that show that time viewed (by a human) is an important factor in advertising effectiveness. If someone is telling you that two seconds is enough, don’t believe them, or at the very least look deeper into their findings and methodological design.

- View duration (or other proxy measures) does not equal human attention.

Even if an ad is viewable (by MRC standards) it doesn’t mean it will be viewed. There is a big difference between what a human looks at and what a vanity metric like view duration might suggest is being looked at.

Put another way, when view duration is used as a proxy for attention it tells us little of whether someone has looked at the ad. In our data we see that around half of an ad has any attention paid to it, and if we use gold standard active attention (eyes on ad only) that number drops to around 20%. What this says is that view duration can equally capture distraction as it can capture attention.

Our second-by-second data reflects why this happens. Ads are not viewed with sustained and undivided attention. Humans switch in and out of active (eyes on ad), passive (eyes on screen but not on ad) and non- attention (no eyes at all) across the entire course of a view. This switching is consistent across every single platform, every single format and every single country that we have collected attention data from.

What is not consistent is the underlying distribution of these three types of attention across these platforms and formats. Some platforms and formats get more active attention and less non-attention, or the inverse. We know that this distribution is directly related to the quality of the ad delivery including (but not limited to) pixels, coverage, and sound.

I actually believe the word ‘view duration’ is deceptive in its meaning and should be renamed ‘impression duration’. This sleight of hand implies a human view, which is wrong and misleading for advertisers.

- The relationship between attention and ad impact transcends boundary conditions (i.e., collection method, collection year/country and dependent variable).

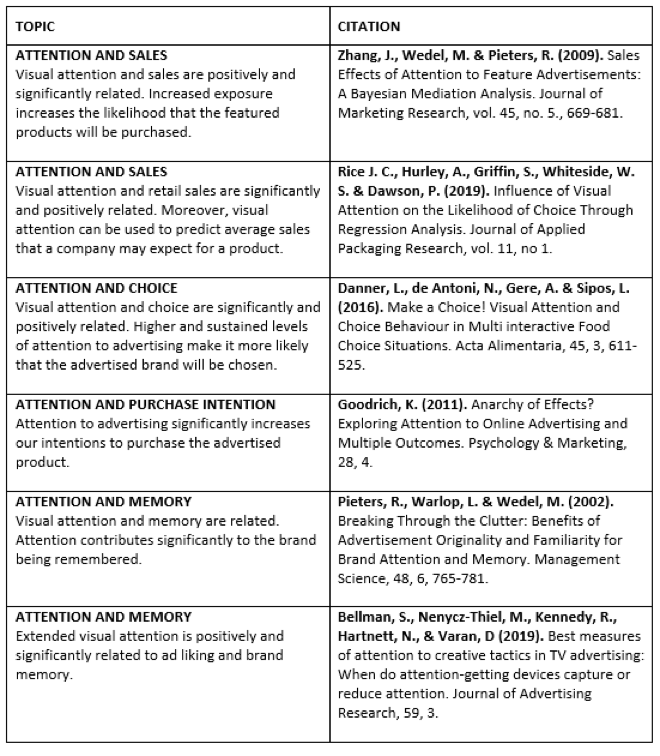

We are not alone as scholars of attention. Fig. 4 offers extra proof points from academic papers with findings similar to some of these, including attention and sales, attention and brand choice, attention and memory and attention and purchase intent.

The application of attention to drive ROI in 2021

Summarising much of the work we have done, and echoing the sentiment of the attention leaders who authored papers in the WARC Planning for Attention Guide (June 2020), here is the problem our ecosystem faces and what it means for advertisers.

What we know:

- Not all reach is created equal

- There’s no transparency around this truth

- Proxy measures don’t cut it

- CPM doesn’t account for performance difference, and

- Relative value can’t be quantified.

What this means:

- Advertisers don’t get what they pay for

- Media spend disappears with minimal value to brands, and

- Our impression system fails advertisers.

In conversation with industry this past year about the ecosystem and how attention might be useful in application, we were told that attention metrics tell a different story from reach and frequency. We confirmed that, if applied properly, attention could be the missing ‘relative quality’ layer in media planning. Relative quality is about understanding performance of different platforms using a common metric of value.

The idea that the application of attention metrics in media planning could begin with a simple grocery unit pricing format was formed. Each platform could be considered by its ability to gain active attention seconds relative to other platforms, and its cost considered in the light of that performance.

Grocery unit pricing is a labelling system introduced to help consumers quickly compare the value of similar, but not identical, products. It’s about standardising cost against a common measure (such as litre) without having to do the complicated calculations. Grocery unit pricing is about informed choice and displaying relative value. If the low sugar variant is more expensive per litre, but the customer is willing to pay for that feature, then so be it.

This is how I see a media agency looking at attention data. If one platform renders more expensive per active attention second, perhaps that platform’s nuances, such as targeting or unduplicated reach, are worth paying more for. Initially, performance relativity was the intent of CPM. That is, the higher the cost, the better the media performance in terms of reach. But CPM no longer has a linear relationship with such performance because reach is no longer the universal measure fitting of the category.

Application is at the heart of change, which is why we are playing a more active role in application solutions. The first cab off the rank is a SaaS platform, called attentionTRACE Media Planner, which is based on the same principles as grocery unit pricing: transparency, simplicity and a display of comparative performance. Here’s how it can make a difference.

Use Case 1: Media Mix Planning

Metric: Attention Adjusted™ Net Reach

The number of Active Attention Seconds paid to any one platform/format are the real net reach numbers, whereas current net reach includes non-attention and passive attention (eyes-nearby) even if the impression is viewable by MRC standards. As such, applying Active Attention (% of Ad Length) as a weighting layer to render an Attention Adjusted Net Reach removes distraction from net reach numbers to provide real viewing rates for OTS, GRP and TARP calculations.

For example:

- Gross reach: 5,000 (defined as total number of people regardless of frequency). Net reach: 1,000 (defined as the number of persons/sets of eyeballs on ad).

- Attention Adjusted Net reach: 1,000*38% = 380.

This can be expanded out to include passive attention (eyes nearby), using a total attention (% ad) calculation. This simply means an OTS will still include a level of ‘opportunity’ (not all eyes on ad), but it is a great deal improved from a typical OTS because all non-attention is removed. If you are wondering about the case for using passive attention, read Use Case 3: Creative Planning.

All the attention numbers and proportions provided in attentionTRACE can be used for performance weighting. This example seems to resonate the most with industry at the moment, most likely because it can be combined with agency reach and frequency data, rather than replace it. In this way it adds a weighting layer to existing media mix planning.

For the moment, advertisers can’t change the reality of the amount of human attention paid to different platforms. Platform functionality largely determines this, but using an Attention Adjusted Net Reach number will help to determine what reach actually looks like across platforms. Media mix decisions can then be made in consideration with other factors, such as brand safety, human verified and aaCPM.

Use Case 2: Budgeting Planning/Negotiations

Metric: aaCPM (Active Attention Seconds CPM)

We know that more Active Attention Seconds matter. In attentionTRACE, the aaCPM is a simple calculation of the CPM used by the agency divided by the number of Active Attention Seconds the campaign selections have harvested (i.e. you can filter by age, gender, category etc.) to determine how you how much you are paying per second of active attention.

The aaCPM identifies whether performance differences between platforms are accounted for by cost. This informs the media allocation chart that displays a recommended proportion of spend per platform relative to this performance across platforms and formats.

Because the relationship between attention and cost is not linear, a platform that on the surface has a lower CPM (as shown in the table below), may actually achieve fewer Active Attention Seconds, therefore a false economy applies.

In another example (see table below), we can see where the industry might start to correct itself. The CPM is the same in this case, but the aaCPM indicates that Platform B is actually more valuable because it delivers more Active Attention Seconds for the money. So, to secure a bid, a buyer might consider paying more for Platform B as it gives twice the Active Attention Seconds. Or at the very least, have a clear idea on where the upper limit for negotiation sits using attention as a quality indicator.

This is the perfect example of where cost and performance are not aligned, and it is why looking at aaCPM in conjunction with Attention Adjusted Net Reach is encouraged to obtain a more complete picture.

Use Case 3: Creative Planning

Metric: Number of Active or Total Attention Seconds

In the Guide to Planning for Attention, Sorin Patilinet, Global Marketing Insights Director at Mars, Incorporated uses an example from Mars where attention in the context of pre-testing renders stellar results for improved ROI. However, attention data can also feed an understanding of different attention environments into the creative planning process.

For example, how much attention do you need to deliver the campaign results? Here are some questions to ask.

- Is your brand distinctive and recognised by more people more easily/often?

- Is the information new or existing?

- Isthiscampaignforshort-termorlong-termgain?

You might need more attention to get new information across. You might be happy with total attention (combination of active and passive) because the brand campaign is established. Plus, the number of attention seconds is a true reflection of the platform experience and/or modal differences. If you know what to expect you can build creative around this reality.

Just three little words: positive attention economy

Attention economics is the study of information overload and its consequences on our economic and social systems. We live in an age of extreme distraction where our capacity to process is limited, so as humans we take decision shortcuts to avoid being overwhelmed. However, taking decision shortcuts is not ideal when you are an air traffic controller, driving big machinery or project managing a bridge construction. In these cases, the study of in-attention is well worth the inquiry.

While it’s not quite the same, and no one is going to die, noise is causing significant in-attention to advertising and it is costing marketers billions of dollars each year in wasted resources. Everyone in our industry is talking about the attention economy, and rightly so – in-attention to advertising is killing our industry. This is why we feel the study of in-attention is well worth the inquiry.

Unlike those other industries, however, the study and application of attention economics in advertising brings with it a dark side. Something that the documentary, The Social Dilemma (2020) reminded us. As Joe Marchese most aptly explains in the Guide to Planning for Attention:

“Heightened competition, superficial metrics and addictive technology have facilitated a race to the bottom where advertisers and brands are incentivized to inundate us with cheap content that has serious repercussions.

“To correct the broken advertising ecosystem, the incentive structure must change so that optimizing for advertising margin does not equate to driving ad dollars to the lowest quality content. We need to better measure quality attention and hold companies accountable for using standards that fairly and equitably value attention.

“The way we spend our time and attention – and the way that time and attention is monetized – is at the forefront of industry conversations. Now, more than ever it’s important to consider how we spend that attention. The business models that will define the next decade and beyond will be predicated on how advertisers, consumers, and the market reconceive what the value of human attention really is in a post-COVID world.”

Just to be clear, we are 100% aligned to this thinking and we are working towards product that drives a ‘positive attention economy’.

Our attention-based media planner rewards quality platforms that work hard to gain human attention and calls out the performance difference of those who don’t. The CPM component is designed to demonstrate the inequity in CPM and performance and to thereby drive CPMs to an acceptable level, not down even further. It is designed to make media planning simple and transparent so that value can be squeezed from each campaign. It is designed to show to the world that proxies, in particular view duration, offer little value to the advertiser and, in doing so, calls to account platforms that shun independent human-based attention measurement in favour of (internally collected) proxies.

In launching the Beta of this attention planning product we talked to a great many industry leaders, as well as the people who drive the actual media planners. Every conversation tells me loud and clear that the industry is ready for a positive attention economy. This is exciting.

Fig 1: Sales Uplift (STAS) and Active Attention Seconds

Fig 2: Active Attention Seconds and Memory

Fig 3: Sales Uplift (STAS) Above and Below 2 seconds

109 Grote Street

Adelaide SA 5000

Australia

www.amplifiedintelligence.com.au